“[the] demands of civilization issue a culture that is a priori rooted in suffering”

-Layla AbdelRahim, Wild Children, Domesticated Dreams (2013)

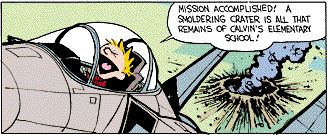

“Today’s schoolyard shootings are disturbing because they are attacks on the

very core of our culture.”

-Mark Ames, Going Postal (2005)

Most kids hate school and adults are generally fine with that.

But given the number of hours, days, and years that children are legally required to be in school, to hate school is dangerously close to hating life. It is not an occasional inconvenience but is their everyday reality. They are pulled from their homes, separated from people they care about, segregated by age, and forced into the company of others who may torment them.

There is almost literally no end in sight for a young person who hates school. Elementary and middle school students may not have the ability to look beyond high school. How very young people experience time is radically different from how adults experience time. And what if, hypothetically, they did have a perspective that allowed them to look far enough into the future to a point when they would no longer be in school? As the saying goes, “if you liked school, you’ll love work”. And if you didn’t like school…then what? This is a situation that must be perceived as a life sentence; a situation where a vast number of young people have no hope and little to lose.

Mark Ames, the author of Going Postal, writes: “[the] misery built into the modern school culture…is so obvious, and so common, that only a kind of adult amnesia, combined with powerful cultural propaganda, could edit away such a widely-held bad memory”

Of course, few young people offer much in the way of resistance to the school system. So-called “good students” acclimate and find that compliance is the least difficult path. They react to ringing bells with the prescribed behavior. So-called “bad students” may sometimes try to avoid classes, refuse to complete assigned work, or perhaps defiantly look out a nearby window to the world outside rather than facing forward. Both sets of students may hate school but their coping mechanisms are not genuine challenges to that which threatens them. The school system knows how to handle both good and bad students.

This is a point that is made after every high-profile school shooting: homicide (and suicide) in schools are statistically uncommon. It could happen anywhere but it generally doesn’t. A child is far more likely to kill or be killed elsewhere such as at home. But Ames writes:

Most Americans know that the low homicide rate doesn’t mean that schools are really safe so much as it reflects effective policing, snitching, and zero-tolerance repression, keeping many more would-be rage murderers, by a factor of tens or hundreds, from crossing the line from plotting to killing.

Success is apparently defined as a situation where students merely wish to kill themselves and others but find themselves unable to do so for one reason or another. This is evident in the immediate calls for gun control. Annette Fuentes, author of Lockdown High, has explained “without guns, Columbine could never have occurred.” True, but somewhat simplistic; without schools Columbine could never have occurred as well. Lack of guns could have averted the massacre but would have done nothing to remove what has been described as a “toxic culture”. The despair felt by students would have remained in place. But again, most kids hate school and most adults don’t care.

Almost by definition, the “well-adjusted” do not resist. Resistance tends to be quite literally a suicide mission. In the face of repression, the well-adjusted tend to, well…adjust. Resistance must then come from those who are not so well-adjusted; those who fail to adapt to the school setting, who find no safe space in the school hierarchy, and nothing to look forward to in the workplace.

These are young people with brains that are still developing, placed in high pressure, arguably intolerable, situations, who feel they have little to lose. It might as well be a social science experiment designed to see what people can endure before lashing out. To quote Ames again:

“The whole country is infested with this meanness and coldness, and no one is allowed to admit it. Only the crazy ones sense that it is wrong—that what is “normal” is not at all normal—and some of them, adults and kids alike, fight back with everything they have.”

Consequently, it is unrealistic to judge their actions based on normal measures of efficacy or even fairness. Rebellions are not always fully understood in the time they are carried out. Indeed, they are not always even fully understood by the people who carry them out. Brenda Spencer was sixteen in 1979 when she opened fire on an elementary school located across the street from where she lived. When asked about her motive, she explained, “I just don’t like Mondays.” And while only the most uncurious of societies would be willing to except that explanation; the explanations that are on offer are not much better.

Furthermore, almost never will the negative consequences of such rebellions fall exclusively on the most culpable; innocent people will almost necessarily be harmed especially when the target is both ubiquitous and abstract. The target is both more and less than the school building, other students, teachers, and administrators. But this harm cannot be laid wholly at the feet of those who resist injustice but must be attributed in large part to those who created and maintained the injustice that generated such violence. When an animal has been place in a cage lashes out, even wildly and without direction, it is the person who locked the cage that is culpable.

The question that we should be asking after each school shooting is not what is wrong with a particular individual who happened to snap before any his or her peers did but rather: what is it about schools that continues to generate such violence?

School violence is not simply a problem but rather a symptom of a problem. Schools are often referred to as a microcosm of society. It is therefore revealing that they are bastions of repression with occasional outbursts of violent rage.